Hello and welcome back to The Fourth Wheel, the weekly watch newsletter that decided not to go to Dubai Watch Week because, frankly, south-east London is lovely at this time of year. What does Dubai have that I don’t? High-rise wonders? I can see Lewisham and Croydon if I crane my neck. Exotic birds? Flocks of ring-necked parakeets whoosh past my office window on a daily basis. Unseasonably warm weather? Thanks to climate change, increasingly so. Sixty international luxury watch brands launching new products and treating journalists to the best hospitality money can buy? Ok, you might have got me there.

But we’re not bothered are we, because this week I’ve got the one and only Jean-Claude Biver in conversation. We spoke recently for a magazine feature, for which only a few choice words were used. So with permission, I’m bringing you the rest of the conversation. I’ve also given some thought to how the GPHG might be improved, with some serious (and less serious) suggestions. Enjoy!

The Fourth Wheel is a reader-supported publication with no advertising, sponsorship or commercial partnerships to influence its content. It is made possible by the generous support of its readers: if you think watch journalism could do with a voice that exists outside of the usual media dynamic, please consider taking out a paid subscription. You can start with a free trial!

Here’s a little taste of what you might have missed recently:

The Only Watch Saga, Part 1, Part 2, Part 3 and Part 4

A Brief History Of Lightweight Watchmaking

Hands-on review: The Patek Philippe 6007G

The Twelve Most Significant Watches In The World

Every Alinghi Racing Watch Ranked From Worst To Best

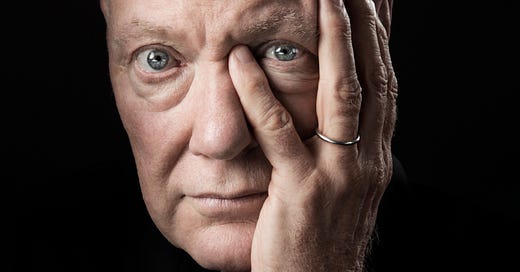

Barely anyone is as well-known in the watch industry as Jean-Claude Biver. His CV is legendary, spanning half a century in the business. It can feel as though if you name any big-brand success story, he was involved. He joined AP the year after the Royal Oak was launched, made his name by reviving Blancpain and selling it for a huge profit in the 1990s and ushered Omega into the 20th century. But to journalists of my generation he was best known as ‘Mr LVMH’1. He ran Hublot, epitomising its loud and proud brand, before taking his inimitable approach to both TAG Heuer and Zenith. He bowed out at the top of his game, as president of the group’s watchmaking division, in 2018, citing health reasons. In a plot twist that surprised no-one, he couldn’t stay away from work, but the nature of his return was eyebrow-raising. The man who had spent his entire career at volume and mainstream brands had his sights set on the high-end indie sector. His eponymous brand, a father-and-son enterprise, debuted on the eve of Watches and Wonders 2023 with an audacious carillon tourbillon that was as technically proficient as it was aesthetically polarising. If I had had a pound for every opinion on it I heard at the fair, I’d have been halfway to a deposit.

The above is only half of the story. Plenty of CEOs have good results to their names, albeit few have as many. Jean-Claude Biver is the dictionary definition of a louder-than-life personality. Tall and barrel-chested, he’s physically imposing (although lost a lot of weight since retirement, hopefully to the betterment of his health) and pairs that with a ruddy complexion and the kind of booming, staccato delivery more commonly associated with political rallies or stadium announcers. If I had to use one adjective to describe him it would be… explosive. There are fireworks displays that are less attention-grabbing than Jean-Claude Biver holding forth; as he makes his points, the journalist in you is paying attention, framing your response and nodding inadequately, but another part of you entirely is concerned about any car alarms, young animals or elderly relatives of a sensitive disposition within a 500m radius. He also makes his own cheese, something which Mr Porter interviewed him on in 2018.

The Zoom call is a poor medium for Mr Biver’s unique delivery. It’s like trying to drink Guinness through a straw, or photograph Jupiter using a pinhole camera. The written word, likewise, robs his full-volume fusillade answers of their true quality. I might, if I can, put some clips on Instagram, but as you read the interview, imagine if you can that the answers are being shouted from the opposite end of a car park, without a megaphone. Aside from the manner of his responses, Mr Biver has never been shy about speaking his mind, and so it proved when we sat down to discuss his new existence as an indie brand founder.

CH: What has becoming an independent brand taught you that your decades in the industry hadn’t already?

J-CB: To be independent teaches me responsibility. When you are an employee, I don't say the employees have no sense of responsibility, but even if they have a sense, the responsibility is never the same as when it belongs to you. When you are independent, you are also alone. If you come to a group, there will always be people on whom you can rely, who you can ask for advice. You can always say, “Yeah, but the team thought…”. Being independent means you really have no way to hide, you have no way to cheat, you have no way to lie. It's the contrary of being in a big group.

This may seem a little bit negative, but it all depends on your character. So many people feel more comfortable to be members of a group than to be alone. Now that I'm independent again – because I have been already with my first brand Blancpain - I can feel what loneliness means. I had forgotten, because I sold Blancpain in 1992, such a long time ago. At Swatch group, at LVMH, I never felt alone. When I had hesitations… well, let’s take the example of recently, the Only Watch decision, to go or not to go. I couldn't ask anybody. I was just alone. And I was too proud. I said to my son, I swear, I said listen, I will make a decision, but not now. Let it go another three to five days. And then we make a decision. And today I can see it was wise and it made sense! [Note: we spoke about four hours before news broke that Only Watch 2023 was cancelled]. Also, to be independent brings a lot of advantages. You never feel better than when something is your own. When you sell a watch for 1.3 million, and it's your own company, you feel quite good. But if you don't sell it, and it remains in the stock, fucking shit! That costs you a hell of a lot. And then you feel really bad!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Fourth Wheel to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.